Leave it to the IRS to hide a tripwire in your cash value life insurance policy. If you’ve been working hard to fund your life insurance so you have an ample stream of tax-free income later in life, watch out. Take one step too far with your premium payments, and the tax perks of that policy could suddenly disappear. That wire gets tripped when you overfund your policy and the IRS converts it from life insurance to what’s called a modified endowment contract or MEC.

What Is a Modified Endowment Contract (MEC)?

A modified endowment contract (MEC) is an overfunded cash value life insurance policy that has more restrictive tax rules than standard life insurance. The MEC came into being in the late 1980s, when the IRS moved to close a tax loophole involving permanent life policies. In years prior, some policyholders would dump cash into their insurance, specifically to benefit from two tax features: tax-deferred earning growth and tax-free distributions.

The IRS shut down that tax shelter strategy by enacting the Technical and Miscellaneous Revenue Act of 1988, also known TAMRA. TAMRA closed the tax loophole by creating:

- The concept of the MEC

- A test to determine when a life insurance policy is reclassified as an MEC

- New, more restrictive tax rules that would apply to all MECs

The tax rules that apply to MECs under TAMRA discourage the intentional overfunding of life insurance to maximize tax-free earnings growth. An underlying goal of the legislation is to reposition life insurance as a tool for estate planning and retirement income — versus a tax-advantaged investment vehicle.

Only life insurance policies that accrue cash value and were entered into after June 20, 1988 are subject to TAMRA and the MEC test. Cash value policies include variable life, whole life, and universal life. Term life does not build cash value and is therefore not at risk of being classified as an MEC. Also, single-premium whole life policies automatically violate the MEC test and are immediately recognized as MECs. Flexible-premium policies are subject to an annual MEC test for the first seven years of their existence. If a policy fails the test, the IRS deems it an MEC and the tax treatment for MECs is applied going forward.

Quick History Lesson on Modified Endowment Contracts

FIFO (first-in-first-out) taxation

One of the features that makes life insurance attractive is the ability to access the cash value during your lifetime without tax implications. Withdrawals and cash value loans from your life insurance are not normally taxable events. You only incur taxes for cash distributions when those distributions exceed the premiums you’ve paid into the policy. And this makes sense. Once you withdraw more than you’ve paid in premiums, you’re tapping into the investments gains in your cash value. And, as you might expect, the IRS is pretty quick to want a piece of those gains.

There’s a subtle tax rule at play here, and it’s called first-in-first-out taxation, or FIFO. FIFO assumes that when you take a distribution from your life insurance, that distribution consists of premiums first and gains second. Say you’ve paid in $10,000 to your policy over 10 years. During that time, your cash value grows to $12,000. That $12,000 consists of the $10,000 you paid in premiums plus $2,000 in gains. If you pull $11,000 from your account, the IRS assumes that withdrawal consists of, first, the $10,000 you paid in premiums and, second, $1,000 in gains. You pay taxes on the $1,000 only.

In the years leading up to TAMRA, abuse of this FIFO taxation was becoming more common. Essentially, you could pump as much money as you could spare into your life policy. You could even pay up the policy in one lump sum, and then start rapidly accumulating cash value without tax implications. In the meantime, if you needed funds, you could pull them from the policy tax-free, as long as the distributions didn’t exceed the premiums you paid in.

TAMRA (Technical and Miscellaneous Revenue Act of 1988)

TAMRA slaps the wrists of abusers by taking away FIFO taxation on policies that exceed the IRS’ limits for funding. Cash value policies are now checked against those funding limits annually for seven years from policy inception. Those annual checks are called the 7 pay test. You might also see it referred to as the seven-pay test, the 7 pay limit, the MEC test, or the MEC limit.

The 7 pay test

The 7 pay test caps the amount of premiums you can pay into a policy in those first seven years. The limit in each year is equal to the total premium required to pay up the entire policy, divided by seven. If you pay less than the premium cap in a given year, that amount is rolled over and added to the cap for the next year. But if you pay more than the cumulative premium cap in any year, the policy fails the 7 pay test and the IRS classifies it as an MEC.

A policy that’s been in force for seven years without failing the 7 pay test is no longer subject to a premium limitation, unless material changes are made to that policy. Material changes include increases to the death benefit, cancellation of a benefit rider, or a partial cash surrender. These types of policy changes would reset the seven-year timeline, making that policy subject to the 7 pay test for seven years after the policy change was implemented.

Notably, a decrease in the death benefit does not reset the seven-year clock, but it would prompt a revaluation of premiums paid in prior years based on the new face value. That could result in a retroactive violation of the 7 pay test.

Exceeding the 7 pay limit

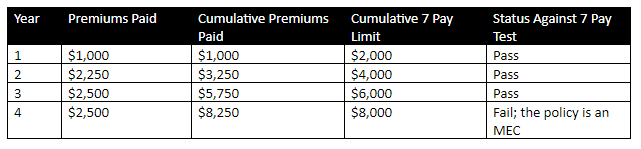

Let’s look at an example of how you might violate the 7 pay test. Say you buy a $100,000 universal life policy with flexible premium payments. Based on actuarial assumptions, the annual 7 pay limit on that policy is $2,000. Now let’s assume you pay $1,000 in premiums in the first year, and $2,500 in the years that follow. As the table below shows, you’d violate the 7 pay test in Year 4.

As another example, let’s say you have a 10-year old variable life policy with a death benefit of $200,000. You decide to increase the death benefit to $250,000. Since you’ve made a material change, your policy is subject to the 7 pay test for the next seven years.

In practice, you probably wouldn’t violate the 7 pay limit unknowingly. Insurance companies regularly perform MEC tests on their policies and would notify you if you’re danger of stumbling into MEC territory. If you ignore those notifications and your policy does fail the 7 pay test, the IRS notifies your insurer and the insurer has a 60-days window to undo the overage. If the insurer returns the extra premium to you, you avoid the MEC classification and retain the tax benefits of your life insurance policy.

LIFO (last-in-first-out taxation)

As noted above, TAMRA gets rid of FIFO taxation for life insurance policies that are deemed MECs. Once reclassified as an MEC, the policy is subject to LIFO (last-in-first-out) taxation. At that point, cash value distributions are considered to be gains first and premiums last. That means the MEC owner will owe taxes on any distributions to the extent the cash value has grown. Those gains are taxed at the MEC owner’s normal income tax rate.

We can use our scenario from above to show how LIFO changes the tax picture. To recap, our policy has a $12,000 cash value, consisting of $10,000 in premiums and $2,000 in gains. A cash distribution of $11,000 under LIFO would consist of $2,000 in gains and $9,000 in premiums. Under FIFO taxation, you only recorded $1,000 in taxable gains — so LIFO, in this scenario, doubles the tax bill.

But that’s not all. The IRS takes a very broad view of what’s considered a “cash distribution.” Withdrawals, loans, and cash dividends from MECs are all taxable distributions. And those distributions would continue to be taxable until the MEC’s cash value falls below the cumulative premiums paid.

Benefits of an MEC

Wait…benefits of an MEC? LIFO taxation sounds pretty severe, so you may be wondering how there could be any benefits to this rogue form of life insurance. It’s a fair question. While TAMRA did take away a few tax advantages of an over-funded life insurance policy, there’s one tax perk TAMRA didn’t touch: the tax-free death benefit.

Death benefit tax exemption

There aren’t too many places you can put your money that guarantee to deliver a tax-free, lump sum payment to your heirs when you die. This feature alone makes the MEC worth a look for the purposes of estate planning. If you have the cash available, you could intentionally overfund a life policy in exchange for the security of knowing your loved ones will be taken care of.

Consider a single-premium whole life policy. Because this policy would be paid up with one premium payment, it’s automatically classified as an MEC. But that single payment also secures a tax-free inheritance for your family. If you have no plans of touching the cash value in that policy, you don’t really care how distributions are taxed. In other words, the MEC classification is irrelevant to you when your sole intention is to set up a death benefit for your heirs.

Leverage large sum of money

You could also use an MEC as a place to hold large amounts of cash. Once a life insurance policy is reclassified as an MEC, there’s no longer any restriction to premiums paid in. You could purchase a rider that adds the cash value to the death benefit and then lean on the MEC as a way to grow your estate tax-free. While there are other ways to invest, hold, or deploy large sums of cash, most of them have tax consequences. An MEC does not incur taxes unless you take distributions.

Liquidity

Cash in an MEC is easily accessible and can be withdrawn or borrowed at any time. Despite the tax consequences of the withdrawals, MEC funds are more liquid than, say, money invested in real estate, businesses, and even mutual funds. In a pinch, you may prefer absorbing the taxes on an MEC distribution over cashing out mutual funds in a market downturn.

Disadvantages of an MEC

While the MEC is potentially useful as an estate planning tool, it’s not a great option for retirement income. Here are three reasons why.

FIFO no longer applies

The main reason you’d want to avoid violating the 7 pay test on your life insurance is to preserve that FIFO taxation. Under FIFO, you can defer taxes on your cash investment gains for long periods of time. But the moment the policy is reclassified as an MEC by the IRS, that FIFO perk goes away. Thereafter, you’d pay the taxes on your cash value gains upfront.

10% tax penalty on withdrawals before age 59 ½

There’s another tax rule that further discourages you from taking distributions from an MEC. MEC withdrawals are subject to a 10% tax penalty if you haven’t yet reached the age of 59 ½. After age 59 ½, the 10% penalty goes away, though you are still subject to income tax on those distributions.

Policy loans from cash value are treated as ordinary income

Loans against your life insurance cash value are usually not taxable as long as you keep your policy active. This rule changes when that policy becomes an MEC. Thereafter, any cash you take from the MEC in any form is taxable as ordinary income. That means you’ll owe taxes — and possibly penalties — on cash dividends, cash withdrawals, and policy loans.

Common Use of Modified Endowment Contracts

Although the IRS created the MEC as a punishment of sorts for overzealous policyholders, the MEC does have a role to play in estate planning — assuming you don’t expect to use the cash value during your lifetime.

As noted, the tax-free death benefit is the MEC’s most attractive feature. But making use of that, without triggering unnecessary tax liabilities, takes careful planning. One popular strategy involves categorizing your assets into three buckets: the money you use now, the investments you’ll use later, and the assets you’ll pass on to your heirs. Under this approach, you can plan for current and future living expenses, while setting aside money that’s earmarked for your heirs.

Here’s a simplified example of how this strategy might work. Let’s call the three buckets now, later and never.

- Now: Your “now” funds are your most liquid and most stable assets. These are the funds you’ll consume within the next five years. A financial advisor would help you define the most appropriate investments for your “now” funds, but suitable options might include cash savings, money market funds, and Treasury bills.

- Later: “Later” funds are structured for longer-term growth and income. If you kept all of your funds in cash and money markets, you run the risk of wealth depletion. Your “later” funds are invested for growth so you’re earning income even as you’re consuming your most liquid assets. This layer might consist of stocks, mutual funds, annuities, and other investments that may be volatile in the short-term.

- Never: These are assets you intend to bequeath to your heirs. You might include your home, art collection, and jewelry in this category, for example. An MEC fits nicely into this mix as a highly liquid component of your “never” assets.

This three-pronged approach to estate planning ensures you have enough cash on hand to protect your lifestyle, while safely maximizing the value of your estate. Adding an MEC provides the additional security of guaranteeing a tax-free, cash payment to your loved ones when you pass.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, your financial and estate goals determine whether you need one of the standard types of life insurance or the more specialized MEC. Life insurance has a range of benefits, but the MEC looks most attractive when both of these conditions are true:

- You have extra cash you won’t need for your own living expenses.

- You are highly motivated to set up a tax-free inheritance for your loved ones.

If you do plan on using your life insurance cash value at any point in time, you should avoid stepping into the MEC tripwire at all costs. Pay attention to how you’re funding your policy and heed any warnings of overfunding that come from your insurer. By keeping your premiums below the 7 pay limit, you retain FIFO taxation and maximize the income potential of your policy.

Know, too, that you can’t change your mind about an MEC. Once a life policy is reclassified as an MEC, there is no way to restore the tax benefits of regular life insurance or to undo the MEC classification. Because of the permanence of MEC classification and the resulting tax implications, you should always consult with a financial advisor when setting a strategy for your cash value life insurance policies.